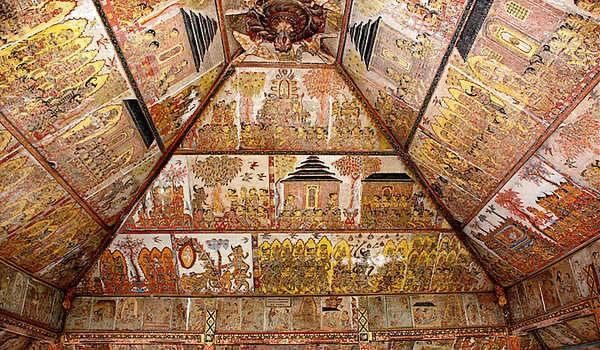

The royal Court of Justice of Klungkung, are a reminder of the power and glory of this former kingdom. These two stately pavilions in their lotus pond gardens at the center of the town of Klungkung, were built in the 18th century, at which time they acted as the island’s highest court of law. Their fantastic ceilling murals in the traditional “wayang” style of painting depict the punishment in hell for wrong-doers, as well as the rewards in heaven for those who are good and honest in their lifetime, depecting a highly evocative view of the Balinese belief in “karmapala” every action bears fruit, be it good or bad. Judgements were made according to traditional law by three Brahmana high priests. During Dutch colonial rule the courts were still held here, pronouncing judgements on cases concerning custom and traditional law which could not be settled at the village level. Meeting were talso had during the full moon of every fourth month of the Balinese calender, attended by the regional kings throughout Bali, where in the high King of Klungkung gave his directives and decisions concerning the problem of the greater Kingdom of Bali. The hall of Kertha Gosa was also often used for audiences granted to guest and foreigners by the King. A tall gateway behind Kertha Gosa once led into Bali’s most splendid palace, which was destroyed in the Dutch bombardments of 1908 that resulted in the conquest of the island. A memorial to this terrible Puputan battle that ended 600 years of glorious rule in Bali by the descendants of Majapahit, has been erected on the eastern side of the Regent’s office, across the road from Kertha Gosa. At the western side of Kertha Gosa pavillion is Taman Gili, which was previously the head-quarters of the king’s guard. Restored during Dutch times, this pavillion is decorated in more recent “wayang” paintings, by the best of the Kamasan School of Artists. The ceilling of this moated pavilion describes the Balinese horo-scopes, as well as illustrating a number of folk tales from the literary classics.

This imposing rectangular pavilion appears to float above its lily-filled moat. Beneath its ironwood shingled roof, every square inch of ceiling is richly painted with traditional “Kamasan style” motifs, and it is only natural to assume that this must be Klungkung’s renowed Hall of Justice. Kertha Gosa is the little square pavilion in the corner of the garden. The Bale Kambang, in the days of the rajas, was headquarters for the royal guards. Later, in Dutch time, anxious relative of plaintiffs and transgressors waited there for judgements emanating from Kertha Gosa. They usually had plenty of time to study the myths and legends pictured on the painted panels overhead. The first of these eight layers of panels shows phases of the astrological calender, while the second tells the story of Pan Brayut and Men Brayut, an impoverished couple who were blessed with eighteen children and didn’t know what to do. All the other layers to the apex relate the adventure of Sutasoma, a semi-divine hero whose wisdom and subtle powers cause arrows and spears, even those hurled at him by the gods, to turn to flowers. He is a Balinese role model of non-aggressive strength. Although the Bale Kambang survived the razing of the palace in 1908, the building seen today is not old. It was completely rebuilt and enlarged in 1942 and, due to the ravages of the climate, some of its ceiling panels were probably replaced even more recently.

Bale Kertha Gosa, the Hall of Justice

The more famous painted ceiling of the Kertha Gosa has also gone through numerous changes this century. It had to be restored after the devastating eartquake of 1917 and was again repainted during the 1930’s by Pan Sekan, a master artist from nearby village of Kamasan. Thirty years later, Pan Sekan’s son, Pan Semaris, directed the total replacement of his father’s weather-eaten ceiling. With the exception of a fee panels added in the last decade, which stand out because of their crudity and the fact that acrylics instead of natural pigments were used, the ceiling is as Pan Semaris, directed it in 1960. In the small pavilion, you find yourself on the bronk of three worlds. Below you to one side is the noisy bustle of modern Bali while to the other lies the old-wordly calm of the water garden, and rising overhead in a pulsating pyramid of richly painted panels is the realm of gods and demonds. During the thirty years of Dutch rule, suspected criminals would be tried beneath these salutary paintings. The panels are arranged in nine layers, the lowest being a series of small panels telling five tales of the Tantri series. Most of the 267 panels relate episodes in the story of Bima Swarga in which Bima, the most unruly of the five semi-devine Pandawa brothers of Mahabharata, ventures into the underworld to rescue the lost souls of his earthly parents. The karmic fate of those who have transgressed is illustrated, while Bima battles with demonds and overtunes cauldrons in his quest. We follow Bima’s journey through the various stages of the heavens in quest of the elixir of immortality that will revive his parents. The entire epic is, in fact, an heroic journey of self-discovery. The astrological calender appears ib some panels, with particular emphasis on eartquakes and volcanic eruptions, which must have on everyone’s mind at the time.