Village-City’ with a Regal History

Denpasar is a “village-city” with an aristiocratic past. Born from the ashes of the defeated Pemecutan court following the puputan massacre of 1906, Denpasar became a sleepy administrative outpost during Dutch times. Since independence, and especially after it was made the capital of Bali in 1958, it has been transformed into a bustling city of some 350,000 souls that provides administrative, commercial and educational services not only to booming Bali, but to much of eastern Indonesia as well. Denpasar is the most dynamic city east of Surabaya, and arguably the richest in thr country—there are more vehicles capita here than in Jakarta.

New city,old villages

Originally a market town—its name literally means “east of the market”— Denpasar has far outgrown its former boundaries, once defined by the Pemecutan, Jero Kuta and Satria palaces and the brahmanical houses of Tegal, Tampakgangsul and Gemeh. Spurred in all directions by population pressures and motorized transport, urban growth is little by little enveloping the neighboring villages and obliterating the surrounding ricefields, leaving a new urban landscape in its wake—housing estates in the midst of ricefields and ricefields in the middle of the city.

To the northeast, urbanisation spills across the Ayung River into the village of Batubulan, famous for is barong dances, where the conservatory of dance has recently been relocated. To the south, the Bukit itself is now subjected to a frenzy of land speculation. To the northwest, it sprawls as far as Kapal, whose beautiful temple now has to be seen above the din and dust of suburban trafic.

This unchecked growth gas swallowed up many old villages of the plain, yet in many ways they remain as they were—their architecture focused around open courtyards, they have intact their intricate temples and collective banjars. The power structure itself, although adapting to new urban tasks and occupations, has also not changed much. Local stariyas, be they hotel managers or civil servants, remain princes—they still have control of land and territorial temples and may mobilize their “subjects” for ceremonies.

Local brahmans are even more powerful—continuing to provide ritual services for their followers and occupying some of the best positions in the new Bali. Thus Denpasar is a showcase of Balinese social resiliency—still “Bali” and worth a visit for its gates, its shrines and its royal mansions.

But Denpasar is nevertheless a modern city. Shops, roads and markets have conquered the wet ricefield areas allowed to be leased and sold by village communities. Here, urbanization has taken on the same features found elsewhere in Indonesia—rows of gaudily-painted shops in the business districts; pretty villas along the “protokol” streets; narrow alleys, small compounds and tiny houses in the residential areas.

Experiment in integration

This new urban space continues to welcome waves of new immigrants—Balinese as well as non-Balinese. As such, it represents an experiment in national integration. Inland Balinese indeed make up the majority of the population. The northerners and southern princes and brahmans were here first. Early beneficiaries of a colonial education, they took over the professions and the administrative positions and constitute, together with the local nobility, the core of the native bourgeoisie. Their villas—with their roof temples, neo-classical columns and Spanish balconies—are the modern “palaces” of Bali.

More recently, a new Balinese population has settled here, attracted by jobs as teachers, students, nurses, traders, etc. Strangers among the local “villagers,” these Balinese are the creators of a new urban landscape and architecture. Instead of setting up traditional compounds with their numerous buildings and shrines, they build detached houses with a single multi-purpose shirne. In religious matters, they are transients—retaining ritual membership in their village of origin, praying to gods and ancestros from a distance through the medium of the new shrine. They return home for major ceremonies, to renew themselves at the magical and social sources of their villages of origin.

Apart form the Balinese majority, there are several non-indigenous minorities in Denpasar, comprising a quarter of the total population. Muslim Bugis came Bali as mercenaries as early as the 18th century. They have their own “banjar” in the village of Kepaon, where they live alongside the Balinese, speaking their language and intermarrying with them. Old men pemecutan will show you a “Bugis” shrine in a small temple near the family cremation site.

The Chinese came early as traders for the local princes. They integrated easily, blending their Chinese and Balinese ancestry. They also have a shrine, the Ratu Subandar or “merchant king’s” shrine up in Batur, next to the shrines of Balinese ancestral gods. New Chinese, often Christians, have arrived, attracted by the booming economy of Bali.

There are also Arabs and Indian Moslems who came in the thirties as textile traders and have since become one of the most prosperous local communoties. They live in the heart of the city, in the Kampung Arab area, where they have a mosque.

Most migrants, however, are Javanese and Madurese, know collectively as “jawa”. They fill the ranks of the civil service and the military (Sanglah and Kayumas areas) as well as the working classes, skilled and unskilled (Pekambingan, Kayumas, “Kampung Jawa” areas). New actors on the Balinese social stage, they introduce new habits—foodselling, peddling, etc. They are also builders of new housing: shacks and tiny houses that bring Denpasar into line with other cityscapes of modern Indonesia.

Thus Denpasar is very much a place where the theme of nation-building is played out. It brings together within earshot of one another the high priest’s mantra, the muezzin’s call, and the parson’s prayer. “Eka Wakya, Bhinna Srutti”—”The Verbs are One, the Scriptures are Many”—so goes the local saying. Balinese tolerance within a national tolerance.

New architectural landmarks

For a look at modern Bali, go first to Taman Puputan square. Facing the museum and the Jagatnatha Temple one sees the heavy-set, new military headquarters. On the far right, the Balinese Catur Mukha ‘God of the Four Directions” gazes impassively through one of its four faces at the statue of the fallen heroes of the puputan. The Javanese-pendopo-styled governor’s residence closes the inventory of power symbols in the center of town. “Chinese” Denpasar and the main markets are a few blocks away, on Jl. Gajah Mada, Jl. Thamrin and Jl. Hasanuddin.

For modern Balinese architecture, do not miss the new administrative complex in Renon. It is landmark made to stay, a projection of Balinese architects into their own future. Go also to the Werdhi Budaya Art Center. New shrine of the island’s culture, it hosts a museum of the Balinese arts as well as stages for dance and theater. On its monumental Ksira Arnawa stage are held equally monumental displays of modern Balinese choreography. For the local color, definitely don’t miss the Pasar Malam Pekambingan night and food market.

Denpasar sights

As a microcosm both of modern Bali and of modern Indonesia, Denpasar is easier to understand than to see. Nevertheless, it awaits the intelligent traveler who wants to learn about the future as well as the past, and who wishes to take home more than just a few images. So forget your lens for awhile. Forget the traditional village Bali; have a look at the new urban Bali.

In the very heart of Denpasar ; just behind the main artery of the city, Jalan Gajah Mada, one can see many traditional compounds, with their gates, shrines and pavilions, in among the multi-storey Chinese shopfronts. Shrines dwarfed by parabolic TV antennas? Gods of the past versus gods of the future?

For a more typical look at Denpasar’s villages, a drive through the streets of the “villages” of Kedaton, Sumerta, and particularly Kesiman will do. Kesiman has some of the best examples of the simple, yet attractive Badung brick-style. Alas, dying witness to a passing grandeur, the Badung brick-style is disappearing, replaced by the new baroque of the Gianyar -style, and the ugliness of rein-forced concrete.

Of the temples, the most ancient is Pura Maospahit, right in the middle of the city on the road to Tabanan. It dates back to the Javanization of Bali in the 14th century. No less temples of the royal families: Pura Kesiman with is beutiful spile gate, Pura Satria and its lively bird market, and Pura Nambang Badung near the princely compounds of Pemecutan and Pemedilan.

A “modern” temple is also worth a visit—the Pura Jagatnatha, right on the central square of city next to the museum. Built as a “world (jagat) temple, its tallest building is a big padmasana “lotus-throne” shrine that symbolize the world as the seat of paramasiwa, the “Supreme Siwa”. Modern Hindu intellectuals meet there for full-moon religious readings — a barometer of Bali’s new monotheism.

Among the palaces, the most typical is the Jero Kuta, which still has all the functional structures of a traditional princely compound. The Pemecutan Palace has been transformaed into hotel. The Kesiman Palace, a private mansion, houses the most elaborate family temple.

For a look at examples of traditional Balinese architecture, one might visit the Bali Museum, right on Taman Puputan square. The good, yet ill-presented collections are kept in builidings illustrative of the Tabanan Karangasem and Badung styles.

Balinese city, Indonesia nation

Nation-building is also very much a Balinese concern. It is “Indonesia” and “development” overtaking Bali. Denpasar is the center from which the national language, Bahasa Indonesia, is spreading to other parts of the island. One speaks Indonesia here interpersed with Balinese words. Through Denpasar, Bali is surrendering its most potent cultural force: its language.

Denpasar is also the breeding ground for a revamped traditional culture. It is here that the concepts of Balinese Hinduism are being re-Indianized by Parisada Hindu Dharma (Religious Council of Hinduism), beyond the maze of Bali’s old lontars and oral traditions. The supreme God, Widhi, here assumes precedence, relegating the ancestors to minor functions. New prayers are taught (Tri Sandhya) and new government priests officiate, called from Denpasar to the villages for the rites of officialdom and for inter-caste rituals. Reversing the old village-based trend, Denpasar is also home to the New Arts. New dances and music are created and taught, spreading into the villages from the city.

Last, but not least, Denpasar is the home of a new breed Balinese. Born to the sounds of a new music, raised in a world of new wishes and desires, taught in the words of a new national language and culture, the young of Denpasar are Jakarta-looking rather than Bali-oriented. Their thoughts take form in a world of Kuta discos and lavish Sanur villas. They are the avant-grade of a new, Westernized Indonesia. Resilience, renewal and decadence-Denpasar will in any case be the stage for a new Bali.

Bali Museum

The Bali Museum’s collections began only in the 1930’s. The Museum Association formaf in 1932, was run by a board of distinguished Balinese, colonial administrators, and representatives of the Dutch steamshpis company, KPM, that brought tourists to Denpasar. With the advent of the war in Europe, colonial interest faded. The museum survived the war and reopened for visitors under the guidance of a devoted Balinese, I Gusti Made Mayun. In the upheavals of the early years of independence, however, nothing was acquired until after 1966, when the museum attained its present status as a provincial museum under the Ministry of Education and Culture.

Bronze Spearhead

These two halves of a prehistoric bronze spearhead are part of the fine prehistoric and historica archeological collection at the museum. The collection of treasured bronzes, stones, and terracottas testify to Bali’s technological awakening and its long established links with the Hindu and Buddhist cultures of Java and beyond

Lake Bratan Bronze

Fragments of an unidentifed bronze were found near Lake Bratan. These probably date from the 13th to 14th centuries

Primitive Art

Expatriate German artist Walter Spies agreed to volunteer as the museum’s first curator. His interest in primitive art ensured the museum’s inclusions of pieces that attest to Bali’s ancient reflecting deep reverence for ancestrors and the forces ancestros and the forces of nature. One primitive pieces is this base for a roof post, from a pavilion in the old village of Sembiran, one the northest coast.

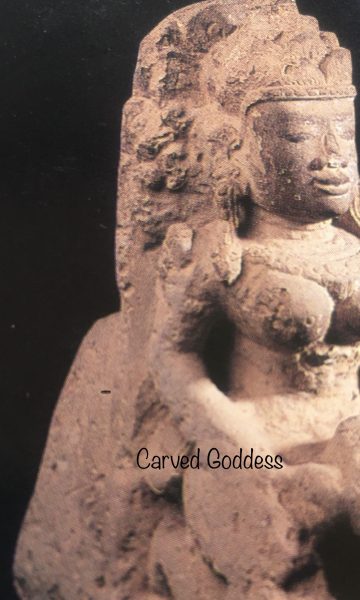

Carved Goddess

The goddess with a tiered lotus crown and elaborate classical clothing is mounted on an animal that served as a water spout. Sturdy stone sculptures in this style are found in a number of sites in Bali, some inscribed with early century dates.

Stupas

Miniature clay stupas with mantra syllables and images, probably impressed from matel stamps, are the earliest evidence of the presence of Buddhism in Bali. This piece may be from the late 8th or 9th centuries.

Revered Figures

This bronze figure of goddess or deified ancestor

Is of a kind sill revered in a number of temples and family shrines today.

Neuhaus Collection

This monochromatic painting, in a style popular in the Batuan area, was acquired from Hans and Rolf Neuhaus, brothers who were interned by the Germans in 1940. The stock of their art and anitque shop in sanur was liquidate, and approximately 1500 objects, from architectural finds to modern art, came to the museum, its largest acquisition ever.

The bali museum’s ethnographic collection outstanding, particularly for its range of stone and wood sculputeres. There are architectural pieces (doors, windows, pillar bases, guardian figures), ritual paraphernalia for temple festivals and life cycle ceremonise and utilitarian objects of considerable ingenuity and charm. There are smaller but significant collections of textiles and traditional paintings, the latter mainly in the Kamasan style.

Chinese Influence

Amusing sculputeres of jovial, slightly demonic Chinese characters acknowlegde the importance of the Chinese to Balimese trade and economy.

Wood Carving

The wooden relief panel, which once probably appeared above a door, features owl in a foliate frame.

Masks

The performing arts are well represented in the museum by an extraordinary range of masks, such as this topeng mask. The collection also included shadow puppets and some stunning musical instruments.

Betel Quid Box

A painting of a refined young gentleman in tranditional costume appers on the lid of a box used for serving the ingredients of the betel quid.

Kris Holder

This painted wood piece from Karangasem is a kris holder representing a heavenly seer.

Terracotta Art

This terrocotta image of a woman’s head is from Pura Belanjong, in Sanur Her ceremonial hiarstyle is broken off.

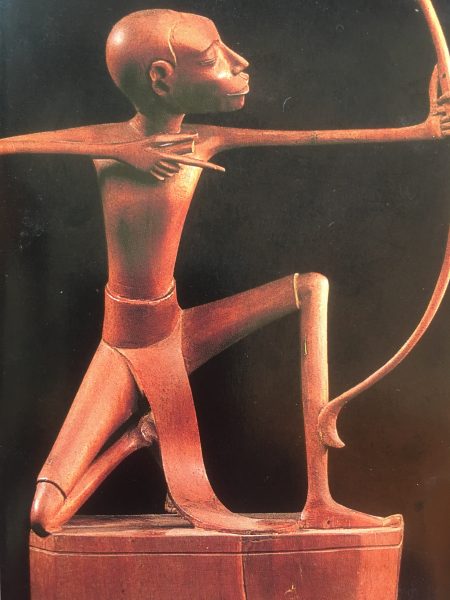

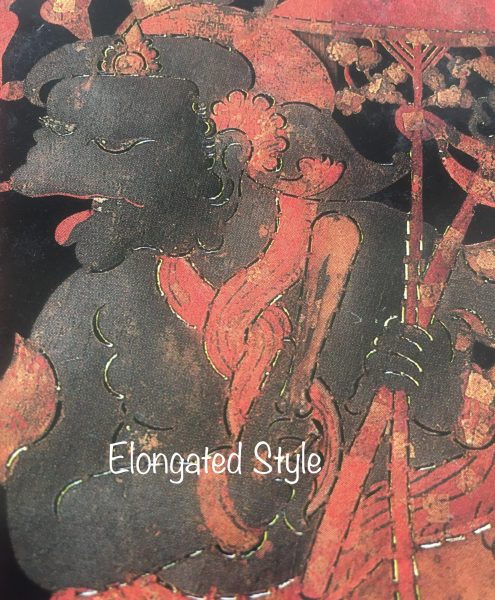

Elongared Style

This youthful archer

Is a superb example of the refiend elongated style of modern sculpture that emerged from the Gianyar era in the early 1930’s During the 1930’s the museum sold selected works by artists of the day to promote contemporary art of high quality. Tourists could inspect the museum’s collection of contemporary work for comparison before purchase. Neither the museum’s influence on the development of modern Balinese art nor is collection of 20th-century pieces should be overlooked.

Denpasar is not an easy place to visit: it’s hot and noisy, and the traffic is a hurtling river of motorcycles and little trucks. For the greatest flexibility, trya combination of taxi, public transport, and walking. Puputan Square. Alun-Alun Puputan, or Puputan Square, is an appropriately empty space commemorates the mass ritual suicide of Badung’s royalty in the face of Dutch cannon fire September 20, 1906 Bali Museum. This well-known destination on the eastern edge of Puputan Square is a good place to be dropped off by taxi. The museum was built by the Dutch after the puputan of 1906 and 1908 as part of their new policy to preserve Balinese culture rather than bombard it to death. The museum’s architecture is itself a subject of this ethnological museum; the buildings incorporate various aspects of temple and palace architecture from different regions of Bali. The collections are very fine, but unfortunately their preservation and display are not.

Pura Jagatnatha. Just next door to the museum, the pura jagatnatha is a temple founded in the 1970’s whose principal deity is Sang Hyang Widhi Wasa, the godhead of the Hindu-Balinese pantheon. Its architecture proclaims Hindu Bali’s underlying monotheism in its single shrine, a towering padmasana, and gives way to ornamental expressionism in the gilded figure of the godhead at the top. For Denpasar’s urban Hindus, many of whom have moved here from faraway villages, its takes thes place of their home temples.

Badung Tourist Information Office. This office is just across the main road from the north flank of Pura Jagatnatha. Their yearly “Calendar of Events” is a list of major temple festivals and holy days, with a schedule of dance performance around south and central Bali. A roundabout at the northern edge of Puputan Square encireles the Catur Muka Monument, whose four faces look in the four cardinal directions. To the north, Jalan Veteran takes you past the Bali Hotel, the island’s first tourist hotel, built by the Dutch in 1982 on the actual site of the puputan. Next door, at Jalan Veteran No. 9, is the textile factory Pertenunan AAA, where kain ikat endek is woven. Father up this noisy street is the bird market in front of the Puri Satria and its noble red brick family temple.

Jalan Gajah Made. Heading west from the Catur Muka statue is jalan Gajah Mada. This is Denpasar’s “best” shopping street, where expatriates used to buy foreign products such as Scotch whisky and cheese. There are interesting shops along here and on Jalan Sulawesi, which meets Gajah Mada just east of the kumbasari market

Kumbasari Market. The commercial crux of Denpasar, this market is southwest of the intersection of Gajah Mada and Jalan Sulawesi. This is a serious market, one that gets roaring at 2am. In daylight hours you can find mountains of things to buy, from gilt-painted parasols with a 7-foot span to scol sacks of cloves and baskets of blue hydreangeas.

Puri Pemecutan. Turning south at the western end of Jalan Gajah Mada, you enter Jalan Thamrin, another important shopping street. At the south end of Jalan Thamrin where it meets the corner of Jalan Hasannudin is the Puri Pemecutan, one of Badung’s key palaces since the 18th century. Today it contains a tourist hotel.

Pura Maospahit. If, at the western end Jalan Gajah Mada you turn right and then cross the street, you will come to the quiet neighborhood of Grenceng. A short walk north brings you Pura Maospahit, a temple of genteel antiquity secreted behind high red brick walls (below). The entrance to this lovely old temple is through a gate about 55 yards along the southern wall. Much of temple was damaged in the 1917 earthquake, and some parts, such as the great carved reliefs on the first gateway, were restored by the Archeological Service in 1925. The central gateway is massive and carved with wonderful delicacy.