Conquests and Dutch Colonial Rule

In the 19th century, Europe took up the fashion of empire building with a vengeance. Tiny Holland, once Europe’s most prosperous trading nation, was not to be left behind, and spent much of the century subduing native rulers throughout the archipelago – a past region that was to become the Netherlands East Indies, later Indonesia.

A stead stream of European traders, scholars and mercenaries visited Bali in this period. The most successful of the traders was a Dane by the name of Mads Lange, one of the last of the great “country traders” whose local knowledge and contacts permitted them to operate on the interstices of the European colonial powers and the traditional kingdoms of the region.

A literary character

Lange was perhaps the prototype for Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim – a man who failed to pick the winning side in an internecine dynastic struggle which wracked Lombok in the first half of the 19th century, but who then settled in southern Bali and found a powerful patron in Kesiman, one of the lords, of the expanding kingdom of Badung. He soon combined his patronage with a knowledge of overseas markets and familiarity with the largely female-run internal trading networks of Bali, to become extremely rich for a brief period in the 1840s.

The Dutch, determined to establish economic and political control over Bali, became embroiled during this period in a series of wars in the north of the island. They came, as they saw it, to “teach the Balinese a lesson,” whereas the words of chief minister of Buleleng best expressed the prevailing Balinese view: “Let the kris decide.” The first two Dutch attacks, in 1846 and 1848, were repulsed by north Balinese force’s aided by allies from Karangasem and Klungkung, as well as by rampant dysentery among the invading forces. A third Dutch attempt in 1849 succeeded mainly because the Balinese rulers of Lombok, cousins of the Karangasem rulers, used this as an opportunity to take over east Bali.

Not wishing to push their luck, the Dutch contented themselves with control of Bali’s northern coast for the next 40 years. As this was the island’s main export region, they did succeed in isolating the powerful southern kingdoms and in controlling much the export trade. Lange’s fortunes soon declined as a result, and he died several years later, probably poisoned out of economic jealousy.

The end of traditional rule

Not long after the cataclysmic eruption of Krakatau in 1883, on the other side of Java; a series of momentous struggles began amongst the kingdoms of south Bali – struggles that were to result in a loss of independence for all of them over the next 25 years.

These conflicts began with the collapse of Gianyar following a rebellion by a vassal lord in Negara. The rebellion ultimately failed, as Gianyar was revived by a hitherto obscure but upwardly-mobile prince in Ubud, but it in turn touched off a series of conflicts that produced a domino effect across the island.

The first kingdom to go was once mighty Mengwi, former ruler of east Java, which was destroyed by its neighbors in 1891. The Sasak or Islamic inhabitants of Lombok then rebelled against their Balinese overloads, which gave the Dutch an excuse to intervene and conquer Lombok in 1894.

Greatly weakened by these events, Karangasem and Gianyar both ceded some of their rights to the Dutch, leaving only the independent kingdoms of Badung, Tabanan, and prestigious Klungkung by the turn of this century.

Shipwrecks, opium and death

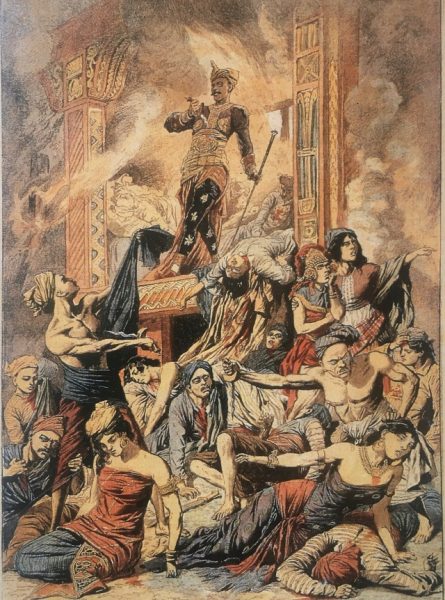

The Dutch found excuses to take on these kingdoms in a series of diplomatic incidents involving shipwrecks and the opium trade. These culminated in the infamous puputans or massacres of 1906 and 1908 that resulted in not only many deaths, but complete Dutch mastery over the island.

In the 1906 puputan, the Dutch at Sanur and marched on Denpasar, where they were greeted by over a thousand members of the royal family and their followers, dressed in white and carrying the state regalia in a march to certain death before the superior Dutch weaponry. As later expressed by the neighboring king of Tabanan, the attitude of the unrelenting. Balinese ruler of Badung, when asked to sign a treaty with the Dutch, was that “it is better that we die with the earth as our pillow than to live like a corpse in shame disgrace.”

A macabre massacre

In 1908 the bloody puputan (meaning “ending” in Balinese) was repeated on a smaller scale in Klungkung. The ghastly scene was one in which, according to one Dutch observer, the corpse of the king, his head smashed open and brains oozing out, was surrounded by those of his wives and family in a bloody tangle of half-severed limbs, corpses of mothers with babies still at breasts, and wounded children given merciful release by the daggers of their own compatriots.

Ostensibly because they felt guilty about the bloody nature of their conquest, which was widely reported authorities quickly established a policy designed to uphold “traditional” Bali. In fact this policy supported only what was seen to be traditional in their eyes, and only if those bits of tradition did not contradict the central aim of running a quite and lucrative colony.

Marketing ploys

Preserving Bali largely meant three things to the Dutch creating a colonial society which included a select group of the aristocracy, labeling and categorizing every aspect of Balinese culture with a view to keeping it pure, and idealizing this culture so as to market it for the purposes of tourism. Although these may sound contradictory, they meshed well together. There were slight hiccups – Balinese who refused to cooperate and did their best to avoid the demands of the Dutch-run state. Some were killed, others were forced to work on road construction projects or pay harsh new taxes on everything from pigs to the rice harvest.

Indirect rule through royalty

Another aspect of “preserving” Bali was that the traditional rulers were maintained. As on Java, the Dutch adopted a policy of ruling the villages indirectly through them, while running their own parallel civil service to administer the towns. At least this was the general ideas, although here too there were some hitches. It took decades before a cooperative branch of the old Buleleng royal family was in place, and many members of the other royal families had to be exiled. In the case of the Klungkung royalty, the exile lasted for some 19 years after the puputan.

The royal families of Gianyar and Karangasem adapted best to the new conditions. Gusti Bagus Jelantik, the ruler of Karangasem, embarked on an active campaign to strengthen and redefine traditional Balinese religion. In large part, he did this to head off the sort of that had earlier occurred in the north, between modernist commoners or sudras who argued for a social status based on achievement, and members of the three higher castes or triwangsa who were given hereditary privileges. Ironically this split came about because of a new emphasis on rigidly-defined caste groups under Dutch rule.

The Dutch had to intervene and exile some sudra leaders, but modernizing moderates such as the Karangasem ruler realized the need to shape and control the changes taking place in Balinese religion and society. In this, they found ready allies among intellectuals in the Dutch civil service with a passion for Balinese culture, and an international influx of artists, travelers and dilettantes who poured into Bali during the 1920s and 1930s.

Hints of sex and magic

Some, like Barbara Hutton and Charlie Chaplin, were rich and famous and stayed only for a short time. Others, like painter Walter Spies, cartoonist Miguel Covarrubias and composer Colin McPhee, are now famous principally because of their long association with Bali.

The attraction for these well-heeled, well-connected or simply talented Westerners was the developing image of Bali as a tropical paradise, where art exists in over abundance and people live in perfect harmony with nature – and image tinged with hints of sex and magic that was officially sponsored by Dutch tourism officials. And it was certainly promoted by genuinely enthusiastic reports from those who visited and witnessed the island’s intricate life, art and rituals.

The positive contributions of foreign scholars and artists, working in conjunction with enlightened Balinese and Dutch civil servants, included such institutions as the Bali Museum and the Kirtya Liefrinck-van der Tuuk (now continuing as the Bali Documentation Center).

But there was a negative side as well. Although the Bali lovers claimed to be the complete opposite of colonial authorities, they in fact represented the other side of the coin of Western rule. With the fan dance performances for tourists came forced labor, and in their writing Bali-struck foreigner always conveniently ignored the poverty, disease and injustice that made the colonial era a time of continuous hardship and fear for many Balinese.