Artifacts and Early Foreign Influences

The early history of Bali can be divided into a prehistoric and an early historic period. The former is marked by the arrival Austronesian (Malayo-Polynesian) migrants beginning perhaps three to four thousand years ago. The Austronesians were hardly seafarers who spread from Taiwan through the island of Southeast Asia to the Pacific in a series of extensive migrations that spanned several millennia. The Balinese are thus closely related, culturally and linguistically, to the peoples of the Phillippines and Ocenia as well as the neighboring islands of Indonesia.

Stone sarcophagi, seats and altars

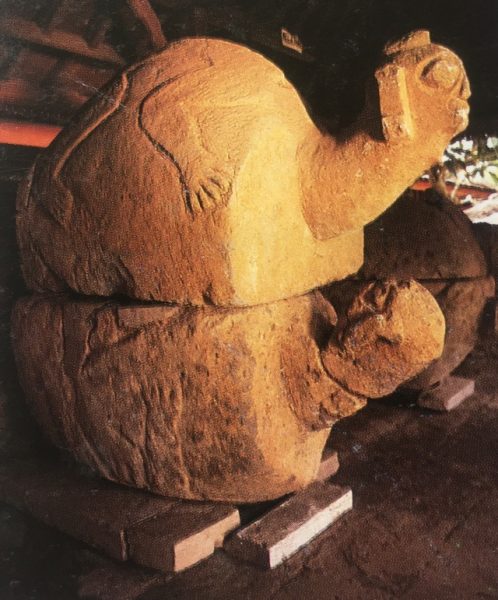

Though precious little is known about the long, formative stages of Balinese prehistory, artifacts discovered around the island provide intriguing clues about Bali’s early inhabitants. Prehistoric grave sites have been found in western Bali, the oldest probably dating from the first several centuries B.C. The people buried here were herders and farmers who used bronze, and in some cases iron, to make implements and jewelry. Prehistoric stone sarcophagi have also been discovered, mainly in the mountains. They often have the shape of huge turtles carved at either end with human and animal heads with bulging eyes, big teeth and protruding tongues.

Stone seats, altars and big stones dating from early times are still to be found today in several Balinese temples. Here, as elsewhere in Indonesia, they seem to be connected with the veneration of ancestral spirits who formed (and in many ways still form) the core of Balinese religious practices.

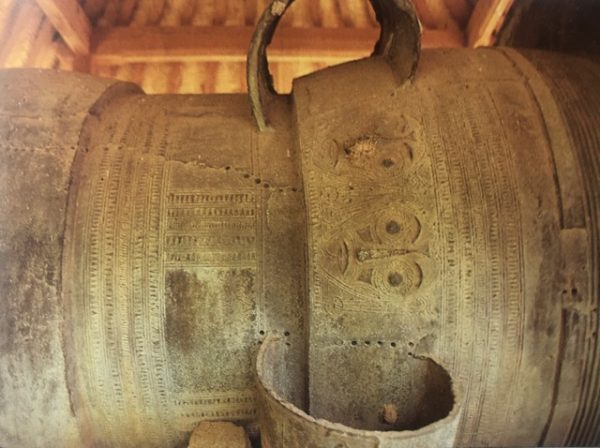

Also apparently connected with ancestor worship is one of Southeast Asia’s greatest prehistoric artifacts – the huge bronze kettledrum known as the “Moon of Pejeng.” Still considered to have significant power, it is now enshrined in a temple in the central Balinese village of Pejeng, in Gianyar Regency. More than 1,5 meters in diameter and 1.86 meters high, it is decorated with frogs and geometric motifs in a style that probably originated around Dongson, in what is now northern Vietnam. This is the largest of many such drums discovered in Southeast Asia.

Hindu-Javanese influence

It is assumed (but without proof so far) that the Balinese were in contact with Hindu and Buddhist populations of Java from the early part of the 8th century A.D, onwards, and that Bali was even conquered by a Javanese king in A.D. 732. This contact is responsible for the advent of writing and other important Indian cultural elements that had come to Java along the major trading routes several centuries earlier. Indian writing, dance, religious and architecture were to have a decisive impact, blending with existing Balinese traditions to form a new and highly distinctive culture.

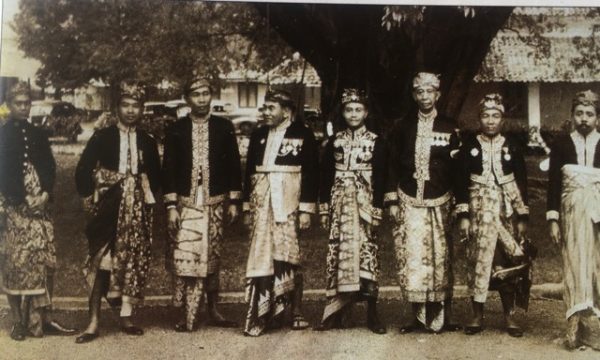

Stone and copper plate inscriptions in Old Balinese are known from A.D. 882 onwards, coinciding with finds of Hindu-and Buddhist inspired statute, bronzes, ornamental caves, rock-cut temples and bathing places. These are found especially in areas close to rivers, ravines, springs and volcanic peaks At the end of 10th and the beginning of the 11th centuries there were close, peaceful bonds with Indianized kingdoms in east Java, in particular with the realm of Kadiri (10th century A.D.to 1223). Old Javanese was thereafter the prestige language, used in all Balinese inscriptions, evidence of a strong Javanese cultural influence. In 1284, Bali is said to have been conquered by King Kertanagara of the east Javanese Singhasari dynasty (1222-1292). It is not certain whether the island was actually colonized at this time, but many new Javanese elements manifest themselves in the Balinese art of this period. According to a Javanese court chronicle known as the Nagarakertagama (dated 1465), Bali was conquered and colonized in 1343 by Javanese forces under Gajah Mada, the legendary general or patih of the powerful Majapahit kingdom who established hegemony over east Java and all seaports bordering the Java Sea during the mid-14th century. It is said that Gajah Mada, accompanied by contingents of Javanese nobles, called aryas, came to Bali subdue a rapacious Balinese king. A Javanese vassal ruler was installed at a new capital at Samprangan, near present day Klungkung in east Bali, and the nobles were granted apanages in the surrounding areas. Javanese court and courtly culture were thus introduced to the island. The separation of Balinese society into four caste groups is ascribed to this period, with the satriyawarrior caste ruling from Samprangan. Those who did not wish to participate in the new system fled to remote mountain areas, where they lived apart from the mainstream. These are the so-called “original Balinese,” the Bali Aga or Bali Mula. Around 1460, the capital moved to nearby Gelgel, and the powerful “Grand Lord” or Dewa Agung presided over a flowering of the Balinese arts and culture. Over time, however, the descendants of the aryas became increasingly independent, and from 1700 began to form realms in other areas.

Reconstructing the past

Because ancestor veneration plays such an important role in Balinese religion, many groups possess family genealogies, known as babad. In such texts, the brahmana, satriya, and wesya clans trace their ancestry to Majapahit kings, while the Bali Aga claim descent from even earlier Javanese rules. There are also groups which claim as their ancestors Javanese Hindus and Buddhists who are said to have taken refuge in Bali from invading Muslim forces. This probably gave rise to the story that entire Hindu-Buddhist populations of Java, with their valuables, books and other cultural baggage, fled to Bali after the fall of Majapahit. We do not know if this is true, as even up to the present day it is a common for families to re-write and improve their babad, depending on their circumstances.

History in a Balinese looking-glass

Most of what we know about Bali’s traditional kingdoms comes from the Balinese themselves. Scores of masked dance dramas, family chronicles and temple rituals focus on great figures and events of the Balinese past. In such accounts, the broad outline of Bali’s history from the 12th up to the 18th centuries is an epic tale of the coming of great men to power. These were the royal and priestly founders of glorious dynasties-some mad, some fearsome, some lazy and some proud-who together with their retainers and family members well as shaping the situation and status of the island’s present-day inhabitants.

It is possible to see the Balinese as both indifferent to history and yet utterly obsessed by it. Indifferent because they are not very interested in the “what happened and why” that make up what we know as history, while at the same time they are obsessed by stories concerning their own illustrations ancestors,Balinese “history” is in fact a set of stories that explain how their extended families came to be where they are. Such stories may explain, for example, how certain ancestors moved from an ancient court center to a remote village, or how they were originally of aristocratic stock although their descendants no longer possess princely titles. In short, they provide evidence of a continuing connection between the world of the ancestors and present-day Bali.

Major events are thus invariably seen in terms of actions of great men (and occasionally women), yet to view them as mere individuals is deceptive. They are divine ancestors, and such their actions embody the fate of entire corporate groups. Above all, they are responsible for having created the society one finds in Bali today.

Each family possess its own genealogy that somehow fits into the overall picture. Some focus on kings, their followers or priests as key ancestors. Others see the family history in terms of village leaders, black smith (powerful as makers of weapons and tools) or villagers who resisted and escaped the advance of new rules.

The fact that such stories sometimes agree with one another should not necessarily be taken as proof that this is what really happened. There are many gaps, loose ends and inconsistencies-often pointing to the fact that generations of priests, princes and scribes have recast these tales about the past to serve their own ends. The stories must be retold, nevertheless, in order to know what is open to dispute.

Ancestors and original

The story begins in ancient Java, in the legendary kingdoms of Kadiri and Majapahit where Javanese culture is regarded (by Javanese, Balinese and Western scholars alike) as having reached its apex. From these rich sources flowed the great literature, art and court rituals of Hindu java, that were later transplanted of Bali.

One of the prime reasons for holding such rituals was to elevate Hindu-Javanese leaders to the status of god-like kings who were in contact with the divine forces of the cosmos. As these Javanese kingdoms expanded to take over Bali, they brought with them their art, literature and cosmology. At the same time, the Javanese also absorbed vital elements of Balinese culture, eventually spreading some of these throughout the archipelago and elsewhere in Southeast Asia.

The great Airlangga, descendant of Bali’s illustrious King Udayana, is said to have ascended the east Javanese throne and to have founded the powerful kingdom of Kadiri in 11th century. Thus it was proper that his descendants would later install priests and warriors from Java to rule over Bali. Foremost among these was the son of a priest, Kresna Kapakisan, who became the first king of Gelgel (now in Klungkung Regency) in the mid-15th century.

The transition to Gelgel from a previous court center at Samprangan (now in Gianyar Regey) was made by a cockfighting member of the Kapakisan dynasty, who became embroiled in a struggle for the throne and attempts to save the kingdom from the mismanagement of his elder brother, or so he account goes. There is little reason to doubt this version of events, yet there are huge gaps in the story of how power moved from Java to Gelgel in previous centuries, and the relation of the Kapakisan line to earlier kings appointed by the Javanese conquerors.

Bali’s “Golden Age”

Most Balinese trace their ancestry back to a group of courtiers clustering about the great King Waturenggong, a descendant of Kapakisan, who is seen to have presided over a Balinese “Golden Age” in the 16th century. Balinese accounts describe him as; “A King of great mystical power, always victorious in war.” European record’s do not mention him by name, but attest to the wealth and influence of a Balinese kingdom which at this time had a more centralized and unified system of government than was the case in subsequent centuries.

Of equal if not greater importance in the collective Balinese memory of this era is the super-priest Nirartha. He is remembered for his great spiritual powers-a man who could stop floods, control the energies of sexuality through meditation, and write beautiful poetry to move mens’ souls. In the genealogies it was he who founded the main line of Balinese high priests – those whose worship is directed to Siwa, Lord of the Gods. His name is associated with many of Bali’s greatest temples, and a corpus of literature produced by himself and his followers.

In Balinese eyes, the descendants of King Waturenggong and Nirartha presided over a period of decline, even though Waturenggong’s son, Seganing, upheld some of his father’s greatness and, after the texts, fathered the ancestors of Bali’s key royal lines. Balinese sources tell of the destruction of Gelgel by a rebellious chief minister, Gusti Agung Maruti, who was distinguished by possessing a tail and an overweening thirst for power. After his defeat by princes who established themselves in the north and south of the island, new independent kingdoms arose from the ashes of Gelgel. The Gelgel dynasty itself survived, albeit in a much reduced state, as the kingdom of Klungkung – maintaining some of its moral and symbolic authority over the rest of the island, but having direct control of only its immediate area.

Slave trading and king-making

To the outside world, as to later Balinese writers, the period following Gelgel’s Golden Age was one of chaos – in which fractious kings ruled from courts scattered about the island. This was not necessary so in contemporary Balinese terms, where the new states must have represented a more dynamic way of conducting the affairs of state and external trade. Bali became famous on the international scene at this time as source of slaves, savage fighters, beautiful women and skilled craftsmen.

According to traditional accounts, the fate and status of present-day Balinese families was also largely determined at this time. Kingdoms rose and fell with alarming rapidity, clans split and were demoted or even enslaved, aspiring princes waged war and organized lavish ceremonies. Such human dramas were punctuated by a series of natural disasters, such as earthquakes, epidemics and volcanic eruptions.

Bali’s principal export throughout the 17th and 18th centuries was slaves. Warfare and a revision of Bali’s Hindu law codes to meet an ever-increasing overseas demand. War captives, criminals and debtors were sold abroad indiscriminately by Balinese rulers, who maintained a monopoly on the export trade. In the north Bali, Europeans were even invited in to oversee the trade, and the Dutch in particular purchased large numbers of Balinese to serve as laborers, artisans and concubines in their extensive network of trading ports – especially their capital at Batavia (now Jakarta), where Balinese slaves made up a sizable portion of the population. Balinese were even sent to South Africa, where in the early 18th century they constituted up to a quarter of the total number of slaves in that country.

Likewise, Balinese wives and concubines were very much favored wealthy Chinese traders, for their industriousness and beauty, and the fact that they had no aversion to pork, unlike the Muslim Javanese. An early 19th-century trader noted that Balinese women were among the most expensive slaves, costing “30, 50 and even 70 Spanish dollars, according to her physical qualities.” The same observer later comments that the Balinese “regard deportation from their island as the worst possible punishment. This attitude results from their strongly-held conviction that their Gods have no influence outside Bali and that no salvation to be expected for those who die elsewhere.”

The principal kingdoms which emerged during this period were Buleleng in the north, Karangasem in the east and Mengwi in the southwest. At various times, these realms expanded to conquer parts of Bali’s neighboring islands. Mengwi and Buleleng moved westward into Java, where they became embroiled in conflict with and between rival Muslim kingdoms. The Dutch came to play an ever larger role in these conflicts, until eventually the Javanese rulers discovered that they had mortgaged their empires to the gin-drinking Europeans. The Balinese were finally pushed out of eastern Java by combined Dutch and Javanese conquered the neighboring islands of Lombok, and at one point even moved into the western part of the next island, Sumbawa. It also annexed Buleleng, and knocked at the gates of Bali’s august, but largely impotent central kingdom, Klungkung.

By the beginning of the 19th century, the island’s changeable political landscape had stabilized to an extent, as nine separate kingdoms consolidated their positions. A massive eruption of Mt. Tambora on Sumbawa in 1815 – the largest eruption ever recorded – proved to be a catalyst. A tide of famine and disease swept Bali in the wake of the eruption, shredding the traditional fabric of Balinese society, and with it many of the fragile political structures of two previous centuries.

Paradoxically, Tambora’s devastating eruption brought in its aftermath a period of unprecedented renewal and prosperity. Deep layers of nutrient-rich ash from the volcano made Bali’s soils fertile beyond the wildest imaginings of earlier Balinese rulers. Rice and other agricultural products began to be exported in large quantities, at a time when vociferous anti-slavery campaign throughout Europe were bringing an end to Bali’s lucrative slave trade.

Two other factors served to transform the island’s political and economic landscape. The first was a dramatic decrease in warfare, as ruling families focused more and more on internecine struggles and competing claims for dynastic control, and the monopolies on duties, tolls and corvee labor that came with it. The second was the changing nature of foreign trade, particularly with the founding of Singapore as a British free trade port in 1819. To Singapore went Bali’s pigs, vegetable oils and rice. Back came opium,Indian textiles and guns. Bali was now integrated with world markets to a degree unknown in the past, a fact that did not escape the ever watchful eyes of colonial Dutch administrators in Batavia.