Nourishing Body and Soul

Nature has endowed Bali with ideal conditions for the development of agriculture. The divine volcanos, still frequently active, provide the soils with great fertility. Copious rainfall and numerous mountain springs supply many areas of the island with ample water year-round. And along dry season, brought on by the southeasterly monsoon, brings plentiful sunshine for many months of the year. Bali is, as a result, one of the most productive traditional agricultural areas on earth, which has in turn made possible the development of a highly intricate civilization on the island since very early times.

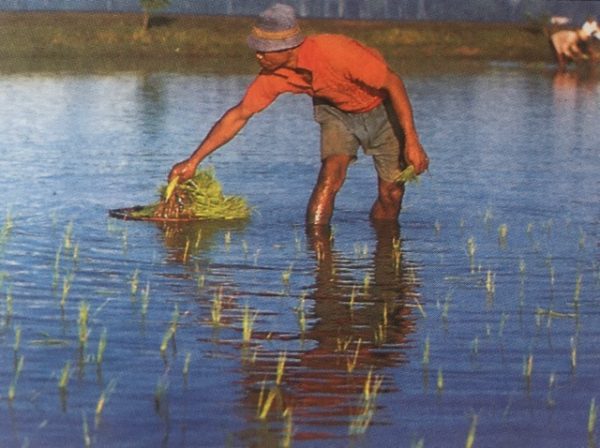

Rice as the staff of life

Wet-rice cultivation is the key to the agricultural bounty. The greatest concentration of irrigated rice fields is found in southern-central Bali, where water is readily available from spring-fed streams. Here, and in other well-watered areas where wet-rice culture predominated, rice is planted in rotation with so-called palawija cash crops such as soy-beans, peanuts, onions, chili papers, and other vegetables. In the drier region corn, taro, tapioca, and beets are cultivated.

Rice is, and has always been, the staff of life for the Balinese. As in other Southeast Asian Languages, rice is synonymous here with food and eating. Personified as the “divine nutrition” in the form of the goddess Bhatari Sri, rice is seen by the Balinese to be part of an all-compassing life force of which humans partake.

Rice is also an important social force. The phases of rice cultivation determine the seasonal rhythm of work as well as the division of labor between men and women within the community. Balinese respect for their native rice varieties is expressed in countless myths and in colorful rituals in which the life cycle of the female rice divinity are portrayed from the planting of the seed to the harvesting of the grain. Rice thus represents “culture” to the Balinese in the dual sense of cultura and cultus – cultivation and worship.

Irrigation cooperative (subak)

Historical evidence indicates that since the 11th century, all peasants whose fields were fed by the same water course have belonged to a single subak or irrigation cooperative. This is a traditional institution which regulates the construction and maintenance of waterworks, and the distribution of life-giving water that they supply. Such regulation is essential to efficient wet-rice cultivation on Bali, where water travels through very deep ravines and across countless terraces in its journey from the mountains to the sea.

The subak is responsible for coordinating the planting of seeds and the transplanting of seedlings so to achieve optimal growing conditions, as well as for organizing ritual offerings and festivals at the subak temple. All members are called upon to participate in these activities, especially at feasts honoring the rice goddess Sri.

Subak cooperatives exist entirely apart from normal Balinese village institutions, and a single village’s rice fields may fall under the jurisdiction of more than one subak, depending on local drainage patterns. The most important technical duties undertaken by the subak are the construction and maintenance of canals, tunnels, aqua ducts, dams and water-locks.

Other crops

One often gets the impression that nothing but wet-rice is grown on Bali, because of the unobstructed vistas offered by extensive irrigated rice fields between villages. This is not so. Out of a total of 563,286 hectares of arable land on Bali, just 108,200 hectares or about 19 percent is irrigated ricefields (sawah). Another 157,209 hectares are non-irrigated dry fields (tegalan) producing one rain-fed crop per year. A further 134,419 hectares are forested lands mostly belonging to the state, and 99,151 hectares are devoted to cash crop gardens (kebun) with tree and bush culture. Compared with the figures for 1980, a gradual decrease in the total area under cultivation may be noted, resulting mainly from population pressures and tourism development. This includes a real estate and building boom in the coastal resort areas and tourist handicraft villages such as Celuk and Ubud.

Other crops include Balinese coffee, famous the world over for its delicate aroma and still an important export commodity. Lately, the production of cloves, vanilla and tobacco has also stepped up, and in mountainous regions such as Bedugul, new vegetable varieties are under intensive cultivation to supply the tourist trade. Other export commodities include copra related products of the coconut palm.

For subsistence cultivators, the coconut palm in fact reminds, as before, a “tree of life” that can be utilized from the root right up to the tip. It provides building materials (the wood, leaves and leaf ribs), fuel (the leaves and dried husks), kitchen and household items (shells and fibers for utensils), as well as food and ritual objects (vessels, offerings, plaited objects, food and drink).

The ‘green revolution’

Recent changes in Balinese agriculture practices have brought fundamental changes in the relationship of the Balinese to their staple crop. Rice production can no longer be expanded by bringing new lands under cultivation. Nor is mechanization a desirable alternative, given the current surplus of labor on the island. For these reasons, the official agricultural policy since the mid-1970s has been to improve crop yields on existing fields through biological and chemical means.

The cultivation of new, fast-growing, high-yielding rice varieties, in concert with the application of chemical fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides, lies at the core of the government’s agricultural development program (BIMAS). Further aims are to improve methods of soil utilization and irrigation, and to set up new forms of cooperative to provide credit and market surplus harvests. Over 80 percent of Bali’s wet-rice fields are now subject to these intensification steps.

Since 1984, Indonesia has able to meet most of its own rice needs, thus relieving some of the pressure responsible for the original “green revolution.” As a result, an ecologically more meaningful “green revolution” is now possible, and rice varieties better suited to local conditions and better able to find an anchor in the traditional system of faith are being introduced to the island.

Since 1988, many fields now display new altars for Sri, and the hope is that her rice cult-one of the basic elements of Balinese civilization and culture-will remain strong well into the future.